Challenger Deep:

On the 25th of March, 2015, it will be the third anniversary of filmmaker and explorer James Cameron's record-breaking solo dive on the Mariana Trench, only the third man in history to visit the deepest point on Planet Earth.

Perhaps you have already seen the movie, "James Cameron's Deepsea Challenger 3D". (Go figure - I took time off work and saw the opening session at a local theater). If not, you can pick up a copy from Amazon or iTunes.

Quick tease, follow this blog for a chance to win the movie or a special t-shirt.

As in past years, around this time my mind frequently goes back to the role that I and the entire team at Opto 22 played in helping put Jim in the pilot's seat of this amazing submarine Deepsea Challenger.

Join me in this and the next few blogs, as I touch on some of the highlights that stick in my mind of this epic adventure.

Jim first seriously considered the idea of building a submarine to go to Challenger Deep (the name of the deepest part of the Mariana Trench) while diving on Titanic.

With him at the time was fellow diver and engineer Ron Allum. Together they roughed out a plan to come up with a faster vessel to dive on the trench than the traditional submarine, which needs to displace a lot of water to move vertically through the water.

Before long, Ron was moving out of a small office and into a nondescript warehouse/factory in the inner suburbs of Sydney, sandwiched between, of all things, a plumbing parts supplier and a plywood factory.

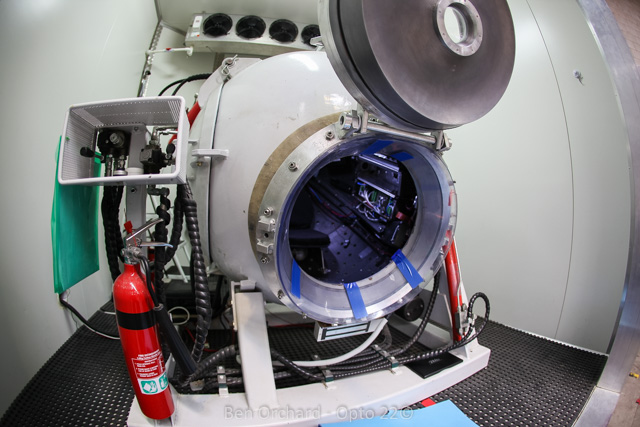

Here is a photo of Deepsea Challenger not long after I got to the factory. Keep in mind that in this picture, the sub is lying down. When it's in the water, it stands upright.

The main pilot sphere is the key to keeping the pilot safe from the crushing 16,000 psi pressure of all the water above him in the trench. He is safe since the inside of the sphere is at 14 psi, ordinary atmospheric pressure. So there are no decompression issues at all.

The rest of the sub is made up of syntactic foam, batteries, and equipment like the thrusters you can see here.

Engineers of different skills were soon part of the team and the decision to select a control system for the submarine quickly came up. Several systems were reviewed, but in the end, Temecula-based Opto 22's SNAP PAC System was chosen because it had a small footprint (space was at a premium in the small pilot's sphere), a very diverse I/O capability, and the ability to easily interface with the many different vendors' parts that would make up the electronics network on the sub.

While the main pilot's sphere was being constructed and tested, a simulator was built to begin testing the electronics. Around that simulator was built a cool room. It looked like this from the outside.

Why a cool room? The simulator was just that, it had to simulate as much of the dive program as you could on land. Other than pressure, the other main challenge for the pilot and electronics was cold, and with that, condensation from the pilot's body and breath. The cool room could take the simulator space down to around 1 deg C (~33F) and lower, if needed, for hours at a time.

Simulated dives of up to 8 to 12 hours were not all that uncommon, so that the life support system and other equipment could be fully tested.

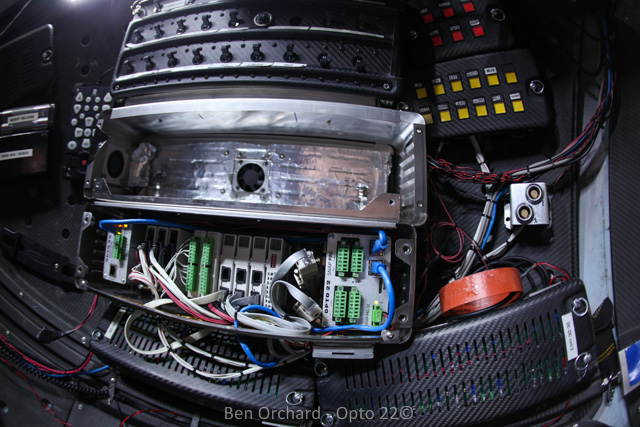

This is what the inside of the simulator looked looked like when I arrived at the factory.

My back is on the pilot seat and I am holding the wide-angle camera where the two-way radio for surface communications would be mounted. Not a lot of space left even at this early stage and not all the necessary equipment was mounted.

The right-hand wall would have the life support system installed; on the left more electronics than what you see here. Along the top are the three video/computer screens the pilot would use to view the video camera feeds, the sonar display, and the Opto 22 graphics for controlling and monitoring all of the systems.

The hardware used is stock standard Opto 22 gear. Nothing out of the ordinary at all. It's the exact same hardware that you can buy today.

Below the rack of Opto 22 hardware are the enclosures for the DC-DC power supplies. Above the Opto, the empty space for the video hard drives. Deepsea Challenger would not be tethered to the ship on the surface, so all of the video camera feeds had to be recorded in the submarine. This is the space for those banks of hard drives.

Above them are the circuit breakers. Fire was the number one safety concern, so all the electronics were fused on both power rails, hot and ground.

To the left is the white control panel for the sonar computer.

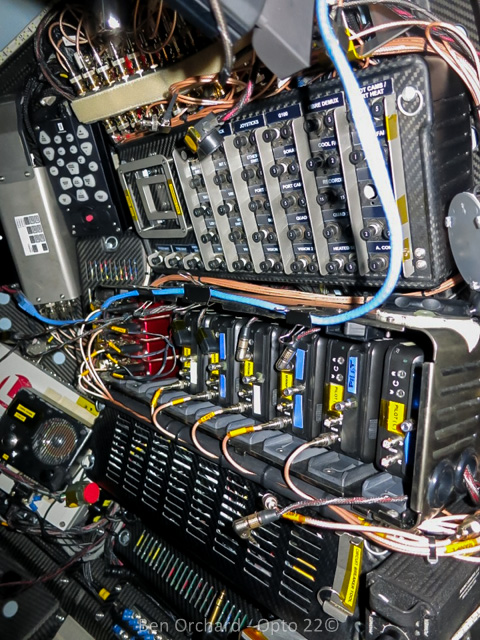

Here is a photo of how the electronics section ended up looking in the sub that made the big dive.

The biggest change is all the video hard drives are loaded into their bay in this shot.

The Opto bay has its cover on just below the video drive bay.

You can still see the sonar hand controller, and to the left of that is the camera fiber-optic-to-coax converter box.

As you can see, space really was at a premium. This is just one of the main reasons why we needed the simulator, to test fit all of the gear required and make the custom length hookup cables for all the different signals.

I ended up back in Australia helping out at the factory because they needed some assistance in fine-tuning parts of the system.

We will talk about some of that in Part 2. Subscribe to the blog so you don't miss it!